The historical source material spans more than three millennia. This period of time can be roughly divided into three social epochs:

– the pre-Confucian of the Shang (about 1500 to 1050 BC) and Zhou (1050 to 256 BC dynasties,

– the Confucian era up to the beginning of the 20th century and

– the post-Confucian era of the Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China.

On a conceptual level, there is a multitude of different healing systems which, with few exceptions, have been handed down and practiced up to the present day. Side by side, sometimes in one and the same medical work, there are theories that attribute the causes of the diseases to the Fall of Man, the influence of demons, a deviation from a normal lifestyle or the malice of deceased ancestors or fellow human beings. But they can also be assigned to different epochs and different social groups.

Ancestral medicine

The earliest sources are oracle bones and turtle shells, which were inscribed around the 13th century BC. From the texts one can see that the causes of diseases were in almost all cases attributed to the possible influence of deceased ancestors or third parties, as well as to malicious magic, i.e. the influence of fellow human beings who were still alive. Appropriate preventive and healing measures are incantations, gifts and gifts of reconciliation. The Shang ruler was a king whose sole responsibility was the questioning and interpretation of the oracles and thus the practice of ancestral medicine. His clientele included the small circle of the ruling elite, and in the case of epidemics, society as a whole.

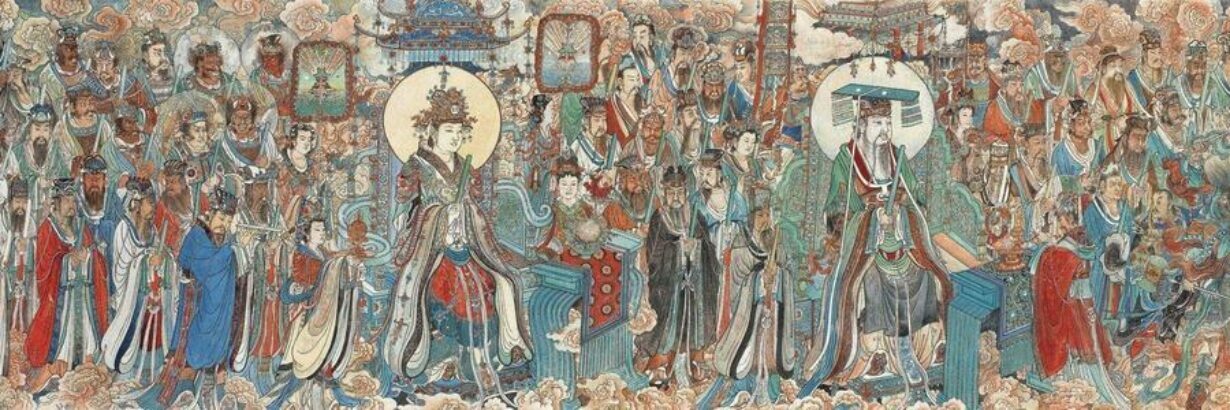

Religious medicine

During the second Han dynasty (25 to 220), various religious systems of healing emerged as aspects of efforts to implement forms of socio-political organization on a theocratic basis. Thus, General Zhang Xiu had established himself as a successful warlord in an area of Sichuan and had begun to set up a new social hierarchy based on both religion and the military. The movement, which initially appeared as a healing cult (Five Bushels of Rice), promoted the idea that illness was the just punishment for past misconduct. However, it is not the dead spirits of deceased ancestors who are responsible for retribution, but certain deities. Above all, repentance is appropriate for them. Therefore, Zhang Xiu imprisoned the sick. They should spend their time in prison to recognize their past sins. Healing was only possible if the sick person wrote down their sins on three pieces of paper, which were placed on a mountain top for the Three Lords of Heaven, Earth and Water, or buried in the ground and thrown into a river. After Chang Hsiu was assassinated by General Zhang Lu, he also built up a theocratic system of rule. Zhang Lu also followed the concept that human misconduct was punished by the gods through illness. Therefore, he allowed criminals to go unpunished until they reoffended a third time. Another cult emerged in the 2nd century AD as the “Great Peace Movement” with Zhang Jiao at the head. His healings consisted of dramatic public mass rituals, during which the sufferers had to confess their misdeeds. Hundreds of thousands flocked to these rituals. In decades of military conflicts, the central government finally smashed the theocratic states. The defense of Zhang Jiao’s supporters went down in history as the Yellow Turban Uprising.

Spirit medicine

A further development of the ancestral medicine documented for the Shang culture led to demon medicine, which can be proven centuries before our era. From it, in turn, the corresponding systematic medicine emerged. The starting point of the healing system of demon medicine is the assumption that diseases are caused by the influence of malevolent demons. On the one hand, the so-called wu magicians knew how to communicate with the spirits of the deceased and sought their advice, especially in the case of health problems; on the other hand to the influencing and expulsion of demons, which populated the universe independently of certain deceased. The medical practice of these wu sorcerers gradually turned into pure demon medicine.

“The demons are ever-present, visible and invisible, using every weakness in humans to attack. Only when the guardian spirits and demons emanating from oneself are strong enough, or when one is able to enlist to one’s aid those beings whose position in the metaphysical hierarchy is higher than that of the attackers, are one protected from the corresponding threats or armed for a counterattack in case of illness.”

Innocence sees demon medicine as a true reflection of the social conditions in the period from the 8th to the 3rd century BC: almost uninterrupted power struggles and the temporary disintegration of China into hundreds of small states that fought “everyone against everyone”. Needle treatment (acupuncture), burning (moxibustion) and massage are probably the original healing methods of demon medicine. The aim of their application was to force the intruders to leave the body. These procedures were later integrated into corresponding systematic medicine. The fight against the demonic attackers was now waged on the basis of “bans” or powerful medicinal drugs. The former were spoken or written down by exorcists or the person concerned themselves; The latter could be ingested or carried as an amulet. The preventive and healing methods based on the basic concept of demon medicine were subsequently recommended for use by authors from a wide range of educational levels and have retained an outstanding status in the medical care of the Chinese population to this day.

Equivalent medicine

The healing systems that can be described as medicine of correspondence are based on the paradigm that the phenomena of the visible and invisible environment are interdependent. Older magical concepts (“correspondence magic”) can be distinguished from later systematic ones. The latter were developed into an increasingly detailed system with the help of the yin-yang theory and the theory of the five element phases. Their foundations correspond in turn to the socio-political ideas of the Confucian state ideology conceived in the same epoch.

Two examples to illustrate correspondence magic (from: Shan-hai ching, “Classic of the Mountains and Seas”, written in the period 8th to 1st century BC): “There is a herb that does not produce fruit. His name is ku-jung. If you eat from it, you will not have children.” – “Bow and crossbow strings help in difficult births if the afterbirth does not occur.”

Previously the influence of demons seemed to be omnipresent, but in the developing systematic medicine, it was the influence and radiation of all imaginable natural phenomena with which one had to live in harmony: points of the compass, stars, food, heaven and earth, rain and wind, heat and cold . An exact anatomy was not developed in this healing system, but rather a highly complicated speculative system of physiological processes that combines the effects and changes of the diverse influences and radiations with the ideological concepts of the yin-yang theory and the theory of the five-element system. tried to connect phases of change.

“The influences taken in from the outside and the body’s own influences are conducted through the organism in a complicated system of pathways. These meridians can be affected by congestion and blockages that may need to be pierced. (…) In metaphorical analogy to forms of organization of the state economy, the organism contains, among other things, so-called “granaries” (cang) and “palaces” (fu), between which a regulated exchange of influences must take place.”

Preventive and curative measures were developed according to this system. Basically, it was about “deriving” symptoms of excess and “filling up” symptoms of deficiency. The aim was to harmonize the currents and changes in the organism. This corresponded to the Confucians’ ideas about the social order. As long as Confucianism was dominant in China, the ruling class protected the corresponding medicine as the only officially permissible one. As a result, an archaic healing system was saved into modern times. The classic written testimony of Huangdi Neijing dates from around the 3rd century BC. In terms of healing techniques, the methods of needling and burning, probably borrowed from demon medicine, are presented here. Some passages contain references to massage, Washes and hot presses. Some medicinal drugs are also mentioned. However, their application was obviously not planned according to the theoretical foundations of corresponding systematic medicine. The experimental systematic integration of certain medicinal drugs into this healing system did not take place until a millennium and a half later.

Natural Medicine

The oldest basic medical works that are still in use today are attributed to emperors who are said to have lived several thousand years before our era. However, these are legends. The Shennong ben cao jing, a herbal medicine, and the Huangdi Neijing, a detailed description of both the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures as well as acupuncture are well known. After the beginning of our era, the Shang Han Lun, a treatise on cold diseases, came into being. It is considered to be the oldest clinical treatise in the history of medicine. A number of famous writings date from the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644), including the Ben Cao Gang Mu, a compendium of Materia Medica.

With the start of the Jesuit mission in the Far East, medical exchange between Europe and East Asia also took off. In Japan, Jesuits had observed native medicine as early as the second half of the 16th century, as evidenced by a wealth of remarks in their letters, the inclusion of Sino-Japanese technical terms in their dictionaries, and a comparison of Western and Japanese medicine by Luis Frois. From the beginning of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), Jesuits also worked in China at the imperial court as astronomers, geographers, painters, architects and mathematicians. In addition to brief explanations in some of her letters, there are extensive translations of Chinese texts published by the German doctor and VOC merchant Andreas Cleyer as Specimen Medicinae Sinicae, sive, Opuscula medica ad mentem sinensium (Frankfurt, 1682) were published. Equally important was the printing of Clavis medica ad Chinarum doctrinam de pulsibus by Michael Boym. The Dutch pastor Hermann Buschoff, who lives in Batavia, wrote the first longer treatise on moxa. Through his writing Het Podagra, Nader als oyt nagevorst en uytgevonden, Midsgaders Des selfs sekere Genesingh of ontlastend Hulp-mittel (1674), which was also translated into German and English, the Japanese word mogusa (Chinese ai) was established as moxa in Europe. The Dutch physician Willem ten Rhijne (1647–1700), stimulated by Buschoff, continued to practice burning therapy in the Dejima branch (Nagasaki, Japan) of the East India Company. His collected work, printed in London in 1683, contains the first detailed treatise on needling, to which he gave the name acupunctura. Stimulated by ten Rhijne, the German physician Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716) also collected further information and materials in Japan, which he published in 1712. His lengthy essays on acupuncture and moxa were widely circulated in the appendix to his book on Japan, which was translated into many languages. While moxa therapy met with great interest, authorities such as Georg Ernst Stahl or Lorenz Heister reacted negatively to ten Rhijne’s and Kaempfer’s descriptions of acupuncture – not least because neither of them got along with the term Qi, so that one could get the impression that the doctors in East Asia would stab in the abdomen to vent intestinal gases. His lengthy essays on acupuncture and moxa were widely circulated in the appendix to his book on Japan, which was translated into many languages. While moxa therapy met with great interest, authorities such as Georg Ernst Stahl or Lorenz Heister reacted negatively to ten Rhijne’s and Kaempfer’s descriptions of acupuncture – not least because neither of them got along with the term Qi, so that one could get the impression that the doctors in East Asia would stab in the abdomen to vent intestinal gases. His lengthy essays on acupuncture and moxa were widely circulated in the appendix to his book on Japan, which was translated into many languages. While moxa therapy met with great interest, authorities such as Georg Ernst Stahl or Lorenz Heister reacted negatively to ten Rhijne’s and Kaempfer’s descriptions of acupuncture – not least because neither of them got along with the term Qi, so that one could get the impression that the doctors in East Asia would stab in the abdomen to vent intestinal gases.

China found itself in a new situation in the second half of the 19th century. Western powers had used armed force to gain access to Chinese markets and waged the first (1839–1842) and second Opium Wars (1856–1860). As a result, Western technology and science penetrated the everyday life of the urban population unhindered. In the cities the number of those who wanted their illnesses to be treated by the imported western methods was no longer increasing by the traditional ones. Those who promised to heal according to ancient crafts were cornered. There were considerations to ban these as seen as a stumbling block to a smooth transition to the western style of effectiveness through rationality.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, there was a state-driven counter-movement under Mao Zedong. It was now a question of providing medical care for the rural population of a huge empire with limited resources. The solution was seen in the maintenance and control of the traditional art of healing, which was particularly widespread in the rural population. New colleges for Chinese medicine were founded, old classics were rediscovered and prepared for the modern age. With the “barefoot doctors” – TCM doctors trained in short courses – medical care was organized across the board.

Only now did the term “Chinese medicine” (中医学) spread, in the English translation with the addition “traditional” and the abbreviation “TCM”. In China, the term often referred less to traditional medicine in the broader sense and more to the newly created healthcare system.

Written and Translated by Daoist Liu Cheng Yong, German Daoist Association.